I recently went to see my eye doctor. It had been a couple of years and I had broken my only pair of glasses as I overzealously cleaned them one morning. I had to make an appointment of course but now, in the age of COVID-19, I had to wear a mask and was instructed to wash my hands as I arrived. Don’t get me started on my opinion on the government edict to wear a mask everywhere I go, but the hand washing was a different request. During my previous appointments, I had normally not touched anything but I respectfully complied. I was greeted by the masked-up office manager who took my temperature, handed me a ballpoint pen in a plastic wrapper and a clipboard and asked me to take a seat to update some personal information. As I sat in the modified waiting area, six feet from the nearest chair, I smiled and shook my head. What a crazy process for a simple eye exam.

Once my information update was completed, I passed the clipboard through a hole in the glass window to the office staff and was directed to either keep the pen or put it in the cup marked “used,” presumably to be disinfected or discarded. Being a pen guy, I kept it. Dr. Tom came out to greet me, looking like he was walking into surgery; scrubs, including a hat, mask, latex gloves, the works. For an eye exam. After the puffer machine (called a tonometer) checked me for glaucoma, the nurse wiped it all down with disinfectant as I followed Dr. Tom to the exam room.

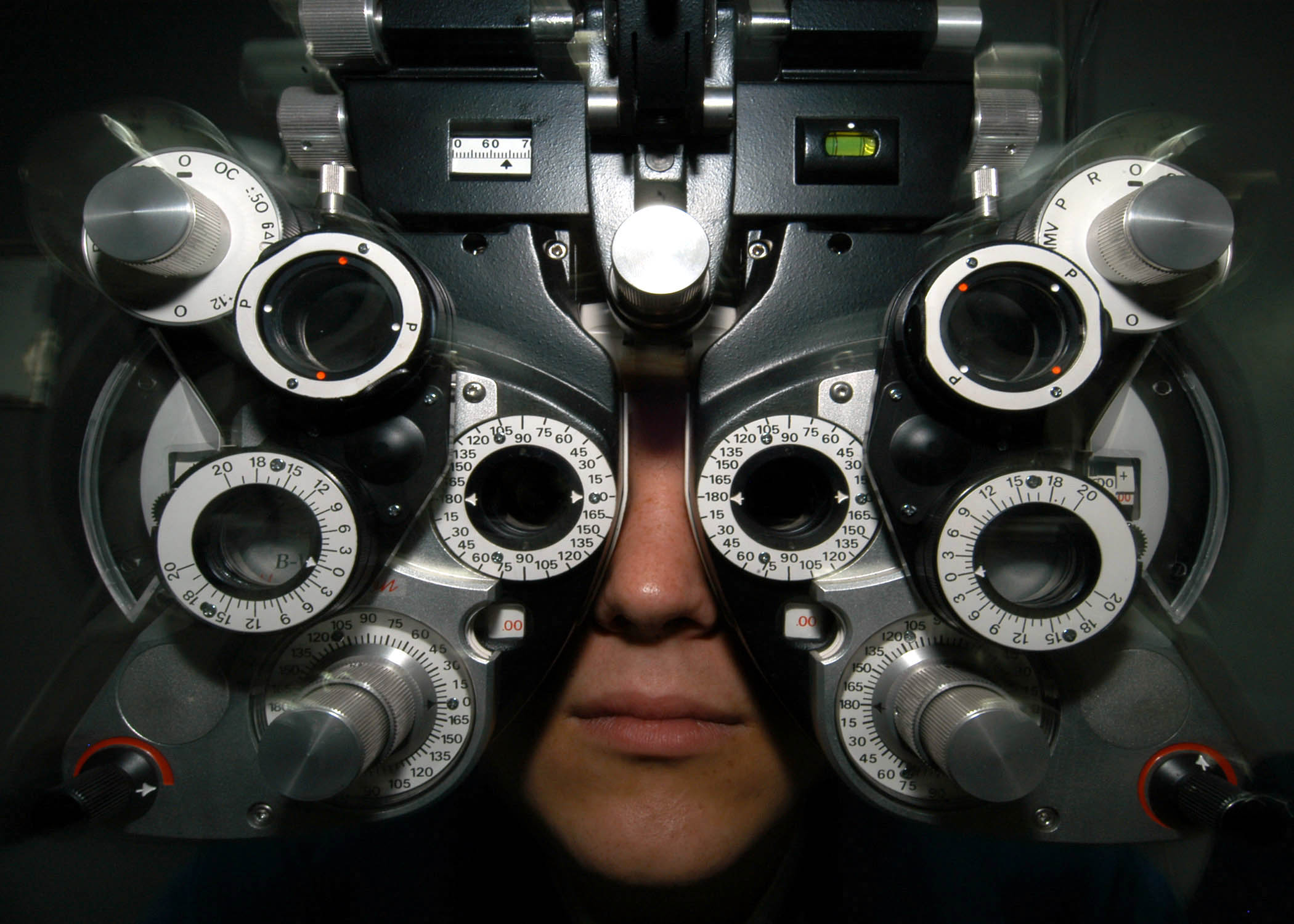

I have long been fascinated with the tools and the process of an eye exam. The tonometer, retinal camera, slit lamp, keratometer, autorefractor, direct ophthalmoscope and lensometer are all important tools in the optometrist’s toolbox to help diagnose and make recommendations so that folks like you and me can see better. (By the way, before this post, I had no idea what any of those machines were called or what they did.) My all-time favorite eye doctor machine is the cool, owl-looking one that snuggles up to my eyes and through which I can see the all-important eye chart. This is the machine where Dr. Tom changes lenses back and forth and adjusts various other settings, while asking me for feedback on which settings give me the best vision – the infamous questions of “what’s better, one or two, three or four? Now, two or four?” Not being an eye doctor myself, I had to consult the oracle of Wikipedia to (a) find out the name of the machine, (b) determine what it does, and (c) ascertain its importance in the grand scheme of things. The sage advised that it’s called a “phoropter,” that it contains different lenses used for refraction of the eye during sight testing to measure “refractive error,” the results of which are used to determine eyeglass prescriptions. Good to know!

As I sat in the exam chair looking through the phoropter at the eye chart and answering Dr. Tom’s questions, I thought about what I do every day as I design estate, business and asset protection plans. Turns out Dr. Tom and I have very similar jobs. Basically, we ask questions for a living. Then we filter those answers through all the technical stuff we learned in school, bringing our education and years of experience working with people to bear on one specific set of issues for one specific individual or family. That process helps us make specific recommendations to create practical, effective, and workable solutions for each personal and unique situation.

I didn’t count, but as Dr. Tom whittled down my options to what would ultimately result in the prescription for my new glasses, it seemed like the questions and choices numbered around twenty five or so. As we do our design work with families, the questions and choices are in the dozens, maybe as many as sixty or so, sometimes more. Some are legal choices that depend on state and federal law, taxes, and money; some are personal preferences that depend primarily on relationships. We arrive at the ultimate decisions by comparing, contrasting, evaluating and assessing all of the options available and filtering those through the “can versus should” analysis.

Decisions like leaving assets outright or in trust, giving beneficiaries’ more control or opting for better asset protection; what distribution standard is best, granting of withdrawal rights, burial or cremation, and who will be your trustee are all questions that are critical to the process. The decisions that determine who takes care of you and your money and who pays the bills if you can’t take care of yourself, who has access to your medical records, end of life decisions and being kept alive on life support, organ donation and what do we do with your “special stuff,” the personal property that many times has more sentimental value than monetary value are all “one or two, three or four” decisions we ask, as if we have our own estate planning phoropter. People, pets, guns, taxes, IRAs, LLCs, type of medical care, asset protection, remarriage protection, flexibility, and legacy questions permeate our discussion to arrive at a framework from which we create a family’s ultimate plan.

Following my time in the exam room, I wandered out to the “showroom” to choose my new frames. No, they weren’t part of the process so far. Yes, there was an additional charge for the frames. And there will be an additional charge when my prescription changes or when I break this pair. Much like updating the estate plan, doing after death settlement work, or serving as trustee when a family member dies. This part of the process was actually pretty fun seeing how good or bad I looked in each frame. This was also where I figured out why I was asked to wash my hands upon arrival. I touched about fifteen pair of frames that the technician had to wipe down and replace on the wall. Sorry about that, ma’am!

Ultimately, I settled for two pair of glasses. One for normal everyday walking around, driving, and watching TV and another for looking at a computer screen from three feet away for most of my day. Dr. Tom the professional said I needed different solutions for my different needs. Yep, sounds right. Like Dr. Tom, we have a knack for identifying important issues and blind spots and creating elegant solutions that solve problems, both foreseen and unforeseen. Unfortunately, I don’t have a phoropter to help.

Douglas G. Goldberg, Esq.

Copyright©2022, Goldberg Law Center, P.C. All Rights Reserved.